Rwanda Genocide's Tough Lessons On 'Othering'

Joining NPR’s Tell Me More podcast is Mishy Lesser. She's the learning director for the Coexist Learning Project and she was in charge of developing the curriculum. Also included in the interview is Joanie Landrum. She teaches English as a second language at East Hartford High School in Connecticut and she used to this film in a lesson for students.

“Creators of the new documentary "Coexist" spoke to Rwandan genocide survivors about forgiveness and reconciliation. Now they're bringing those lessons to American students.

CELESTE HEADLEE, HOST:

This is TELL ME MORE from NPR News. I'm Celeste Headlee. Michel Martin is away. The nation of Rwanda is marking 20 years since the genocide that claimed more than 800,000 lives. And decades after the killing, survivors on both sides are learning how to forgive and how to be forgiven. But it's a complicated, painful process for everyone involved.

FATUMA NDANGIZA: Much as we are doing reconciliation, we still have peace spoilers. People want to spoil peace. People are still die-hards. Some people who committed genocide - but up to now, they don't feel remorse for what they did.”

Continue reading or listening at NPR.

Mass graves honor victims at Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre

April marks 20 years since years of discrimination and hatred escalated into genocide. More than half a million people were killed in 100 days, many of the victims are buried in mass graves at the site of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre (pictured above) where they are remembered in a permanent museum. Human Rights Watch has just issued a new report on how Rwanda and Rwandans are progressing, with a special focus on justice after genocide. You'll find a summary here and you can read the full 20 page report here. This April you'll also be able to watch the new 20th anniversary commemorative edition of our documentary film Coexist. Broadcast information is available on our website here.

New Trailer Released

Check out the newly released trailer for the soon-to-be released hour-long edition of Coexist, coming to a TV near you in the Spring!

Check out the newly released trailer (below) for the soon-to-be released hour-long edition of Coexist, coming to a TV near you in the Spring! Please share it, tweet about it (@coexistdoc), post your thoughts on our facebook, and tell your friends.

It's been a busy summer and early fall for the Coexist team. We're fresh off workshops at the Massachusetts Teacher's Association Conference and an amazing time spent working with the staff and education teams of South Africa's Holocaust and Genocide Centres in Durban, Cape Town, and Johannesburg.

Much more come this fall as we present at conferences in Waterloo, Ontario, Daytona Beach, Florida, and St. Louis Missouri. More details are available here: upstanderproject.org/screening.

Portland’s Rwandans remember genocide

During this 19th anniversary commemoration period of the Rwanda genocide, which began on April 6, 1994, we remember the victims, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis slaughtered alongside tens of thousands of pacifist Hutus.

“In 1994, more than 800,000 members of the Tutsi tribe were killed by Hutu extremists over a period of 100 days.

Nineteen years later, Rwandans living in Maine and in their homeland are still grieving and trying to recover from one of the worst genocides in Africa’s history.

About 200 Rwandans currently living in the Portland area gathered Sunday afternoon to honor the memory of those who died, and to remind future generations that they must remain vigilant to prevent another tragedy.

“We need to keep vigilant and to keep monitoring. It can happen again,” said Jovin Bayingana of Portland, a genocide survivor. “It’s like a volcano that can blow at any time.’”

Continue reading at the Portland Press Herald.

Commemorating the genocide in Rwanda

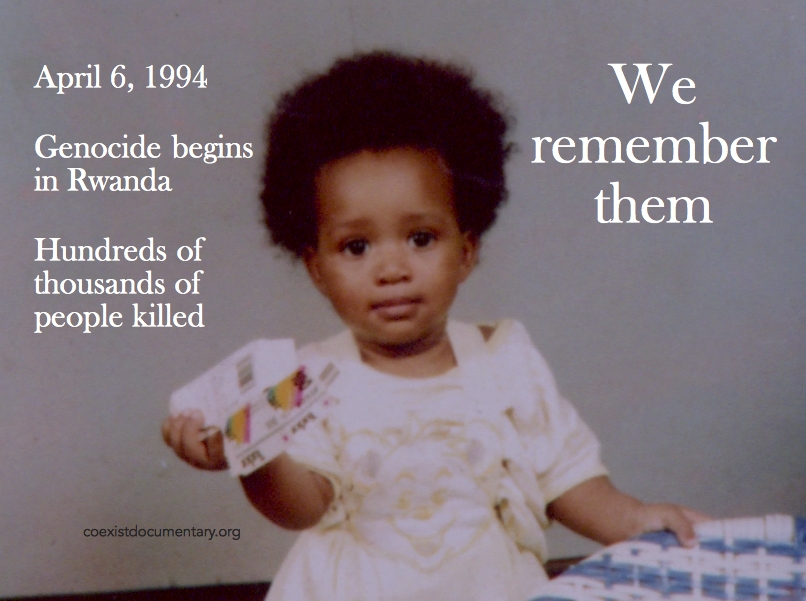

Commemorating the 19th anniversary of the Rwanda genocide with a tribute to a young victim of the slaughter. Coexist is a documentary and educational outreach project in use by more than 3,000 schools and community organizations in 50 states and more than a dozen countries.

On this 19th anniversary of the Rwanda genocide, which began on April 6, 1994, we remember the victims, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis slaughtered alongside tens of thousands of pacifist Hutus. To honor the survivors and remember the victims we will share our documentary film, Coexist at a commemoration event in Portland, Maine on Sunday, April 7th at 3pm. Find more info on our screening page.

Tolerance is language

-Del Dios Middle School, Escondido, California

Coexist learning director Mishy Lesser spent two days with teachers, counselors, and students at the Del Dios Middle School in Escondido, California this week. Escondido is a city of 144,000 people, located in a shallow, "hidden" valley northeast of San Diego. It is one of the oldest cities in the county. According to the 2010 Census, Hispanics are almost half the population in the city but in the middle school, teachers say Hispanic students comprise over 60%. In 2006, the city agreed not to enforce an ordinance that tried to ban landlords from renting to undocumented immigrants. A coalition formed to challenge the legality of the ordinance, and the city backed down. Escondido was ranked the eleventh most conservative city in the US in 2005 by the Bay Area Center for Voting Research.

Here are Mishy's thoughts on the experience:

The social reality here in complex: the students I meet are African American, Pacific Islanders, Asian, White, Hispanic with deep ancestral ties to the valley, Newcomers from Mexico with legal status and considerable economic resources, and children of undocumented Mexican workers, known by some here as illegals. There are 19 elementary schools, 5 middle schools, and 7 high schools. One of the first things teachers tell me is that students who are the children of undocumented workers often repeat the refrain, "I'm not going to college. I'm Mexican." I am eager to meet all the Del Dios students and know I'll get my chance on Monday. For now, my focus is on working with their teachers and counselors and the school principal to introduce them to Coexist and our work bridging genocide to all forms of "othering."

An educator, Janice Lee opened the workshop with a story about the recent parent conferences led by her 8th grade language arts students. At the time, Janice had been working with her students on Rwanda and Coexist for over a week and she asked her students what they will share with their parents about Coexist during the conferences. A brainstorm followed with prompting questions about Coexist and its connection to language arts. One student, a girl, burst forth and said, "I got it. Lanuage Arts is about tolerance. That's it. Tolerance is not just an act; it's a language."

Our Saturday teacher workshop lasts almost seven hours, one hour longer than I'd planned. I have three goals: introduce them to the film and Teacher's Guide; make connections between the film and the lives of their students; and enlist the participants as consultants to this project. We are a small group of nine: teachers, counselors, the school principal, plus a literacy coach and counselor from another nearby middle school. I am thrilled to have the counselors in the workshop because of their mandate to address "othering" or bullying in their schools, and the important perspective they bring to the complex forces that shape the socio-economic, cultural, and emotional lives of their students. The reason the workshop goes over in time is, in part, because the teachers and counselors are eager to talk about the fissures that course their way through the school culture, whether manifesting in speech or behavior by faculty, students, district, or the city. While I've come here to talk about our film on post-genocide Rwanda and introduce them to our Teacher's Guide, we can hardly have a meaningful conversation unless we look at how dehumanization, humiliation, internalized oppression, unquestioning obedience to authority, the routinization of violence and cycle of violence, revenge, forgiveness, and reconciliation play out in their local reality.

We begin by building community and creating trust, and sink more deeply into the work with help from a two-part Pair/Share activity on othering (both when we've been othered and when we have othered) and upstanding (both when we've stepped in prevent harm and when we've felt paralyzed and unable to step in).

I introduce the group to Circles, explain their origins among First Nation Peoples of North America and the role of the Talking Piece, and we begin to pass around the beach stones I brought from the New Hampshire shores. The first rounds of questions give us a chance to examine the behaviors, speech, and actions they both appreciate and are troubled by from staff, teachers, and students that challenge and reinforce stereotypes. We also look at behaviors that reinforce upstanding and those that reinforce bystanding.

I introduce the participants to the genocide in Rwanda through a simulation activity and then we create a group definition of genocide, starting with the human capacity for brutality. We underscore the deliberate nature of genocide, role of dehumanization, routinization of cruelty, and unquestioning obedience to authority. I ask who gets dehumanized here in Escondido, who gets othered in both the school and larger community, and who they include in their community of compassion.

During lunch participants watch the Rwanda history video and Coexist, and do a quick Pair/Share so they can talk about what struck them in the film. We review some of the learning activities in the four lessons of the Teacher's Guide and materials in the Resource Section. I give them a choice of talking about one of the quotes contained in Lesson 2 of the Guide and they decide to drill down into Domitilie's quote:

“Probably they want to show the whole world that there’s peace in Rwanda. But for sure…the victims are still in danger. The hands that killed still intend to kill once again.... They are still threatening us even though we gave them our hearts and showed them that we understand that the previous government forced them to do what they did. But they're not understanding.... They're still randomly killing genocide survivors.”

We are beginning to run out of time so I quickly introduce them to a variety of themes from Lessons 3 and 4. We briefly talk about how they would measure the success of our work together, and have a final circle to talk about how they might envision moving this work beyond the classroom to address othering in the larger school system and community.

Working with Del Dios Students On Monday, I work with 140 eight-graders, most of whom are students of Ms. Lee, the lead organizer of the teacher professional development workshop. She has been working the theme of genocide and Rwanda for three weeks and I have her first group for 90 minutes. The other classes last 45 minutes. In the final class we are joined by another teacher and her journalism students. The room is packed.

The students were for the most part, impressive, knowledgeable, animated, curious, collaborative, and able to connect the material about Rwanda to their lives and experiences. And some students seemed painfully shy, like they wanted to remain invisible in this conversation. I did my best to make them feel safe, pull them into the conversation, yet not intrude on their mode of participation. In all 5 classes, we developed a group definition of genocide and used a simulation activity to review the key facts about the genocide in Rwanda. We talked about bystanding and upstanding, how today's victim could become tomorrow's perpetrator if there is a culture that rewards revenge rather than the slow and complicated and bumpy road of reconciliation and forgiveness. I underscored the role of name-calling and scapegoating in Rwanda and asked how those behaviors played out in their school. We made a list of all the groups that exist in the school and the teachers and counselors were surprised by the number and breadth of groups named by the students. We ran out of time just as we were beginning to talk about the groups that are most vulnerable and invisible at school, and what it would take to protect them.

We can see already how Coexist is rippling through the Del Dios community from Amy who works with students on the newspaper. She shared with other teachers a major shift for the publication "The journalism students and I were very moved yesterday. A unanimous decision to scrap our current spread in the "Be the Change" section and shift to a focus on 'Circles of Compassion' was made. We look forward to highlighting and celebrating how Del Dios shifts into a culture of up-standers and compassionate people in the paper!"

We'll keep sharing what unfolds at Del Dios and other schools as we learn more.

-UP Learning DirectorMishy Lesser

Once a Killer Always a Killer?

“I needed that.” a young woman says under her breath as she walks away from an intense discussion about remorse, revenge, reconciliation, and forgiveness. 40 women and of all ages in 2 separate groups spent 4 hours reflecting on Coexist in a cold, florescent lighted gym in Athens, Tennessee. They wrestled with the moral questions raised in the film. You could see the deep thought on their faces as they contemplated whether men who killed were truly remorseful and actually reconciling with survivors left behind after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

Raven, a mother, connected with the story of Agnes, a mother who lost her husband and three children during the genocide. Agnes chose to forgive those who harmed her. Raven said, “If Agnes can forgive, it makes me think about when I can forgive for the small things that we get worked up about.” Another woman added “and we all have things we can forgive people for.”

It's a lively discussion where the women sit facing each other in a circle, seemingly feeling free to disagree with each other, as they do strongly when one says, “once a killer always a killer.” She's echoing the statement of Elisabeth in Coexist, whose brother was murdered more than decade after the genocide. Immediately many women try to jump in to dispute that, then going around one by one, many express their views that a person can change and not be defined by the terrible act they committed.

As the discussion ends and the women share how they're feeling many express their gratitude for having the opportunity to consider their values and engage in a dialogue about issues that they don't often have opportunities to discuss in a safe space. The women leave with smiles and handshakes, offering their thanks.

Then the men move in for a screening and discussion. This time we don't sit in a circle. But we do get into an intense conversation about whether people are born killers, and Elisabeth's comment “once a killer always a killer.” This is something the men seem keenly interested in debating. Some men point to people like Charles Manson and others known for killing numerous people. Others raise the idea that anyone would kill given the opportunity, with some disagreeing saying they would only kill if their life was at stake, not simply if the opportunity presents itself. There's also some spirited disagreement about whether a local genocide organizer, Gregoire, was truly remorseful and whether Jean, who admits to leading a group who killed, was really reconciling and remorseful.

The men were keenly interested in the motivations and values of people who killed whereas the women were clearly more engaged in the conversation about why some choose to forgive, while others do not. The women also chose to spend more time considering the remorsefulness of men who harm others.

As the men leave offering their thanks and many kind words, I flash back on what our host said when we walked through the halls entering the gym this afternoon, “If anything bad happens you just go over by the door there and let me deal everything and someone else will get you out of here, we'll leave it cracked open.”

But the warning now seems unnecessary, the people we met were cordial, kind, and appreciative at the Athens, Tennessee jail, even though they may be spending many months or years living there.

On the Road with Social Studies Teachers

Hundreds of New England’s social studies teachers gathered in Sturbridge, Massachusetts for a conference (NERC 43) on the role and future of social studies in early April. We were honored to have dozens of those teachers join us for a Special Screening of Coexist, which was moderated by David Bosso, Connecticut Teacher of the Year and Conference Co-Chair. Filmmaker Adam Mazo and I led a simulation to demonstrate how to teach the film, using activities from the Coexist Teacher’s Guide. Karen Cook of Norwich Free Academy in Connecticut sums up why so many educators find Coexist to be a powerful teaching tool by saying, “To see and hear people talk about their own experiences is especially humanizing and an important element in education.”

Teachers at NERC 43 were especially interested in new ways to teach genocide and colonial legacy. One teacher from Weston, Connecticut, Amanda Quaintance, referenced the connection between Alexander’s story in Coexist and the lives of her students. (Alexander is a bystander who participated in violence during the genocide by burning down the house of his neighbor.) “Alex gives us a great opportunity to talk about claiming mistakes whether it’s about a child running down the hall or something more serious.”

Teachers were also eager to explore how to make the connection between genocide and bullying. Former nun and author Barbara Coloroso says the common denominator between genocide and bullying is contempt. “When institutional and situational factors combine with a murderous racial, ethnic, or religious ideology rooted in contempt for a group of people, then bullying is taken to its extreme. The bullies are now well on their way to setting the stage for the dress rehearsals that precede a genocide.”[1]

We love when social studies teachers invite us to screen Coexist because they go deep into critical thinking and promotion of awareness of global issues, as well as social activism.

--Mishy Lesser, Upstander Director

[1] Coloroso, Extraordinary Evil A Short Walk to Genocide, 55-56, as quoted in Lesson 3 of the Coexist Teacher’s Guide.